A talk with Design Jatra- A Community Organization

- Please tell us briefly what Design Jatra is.

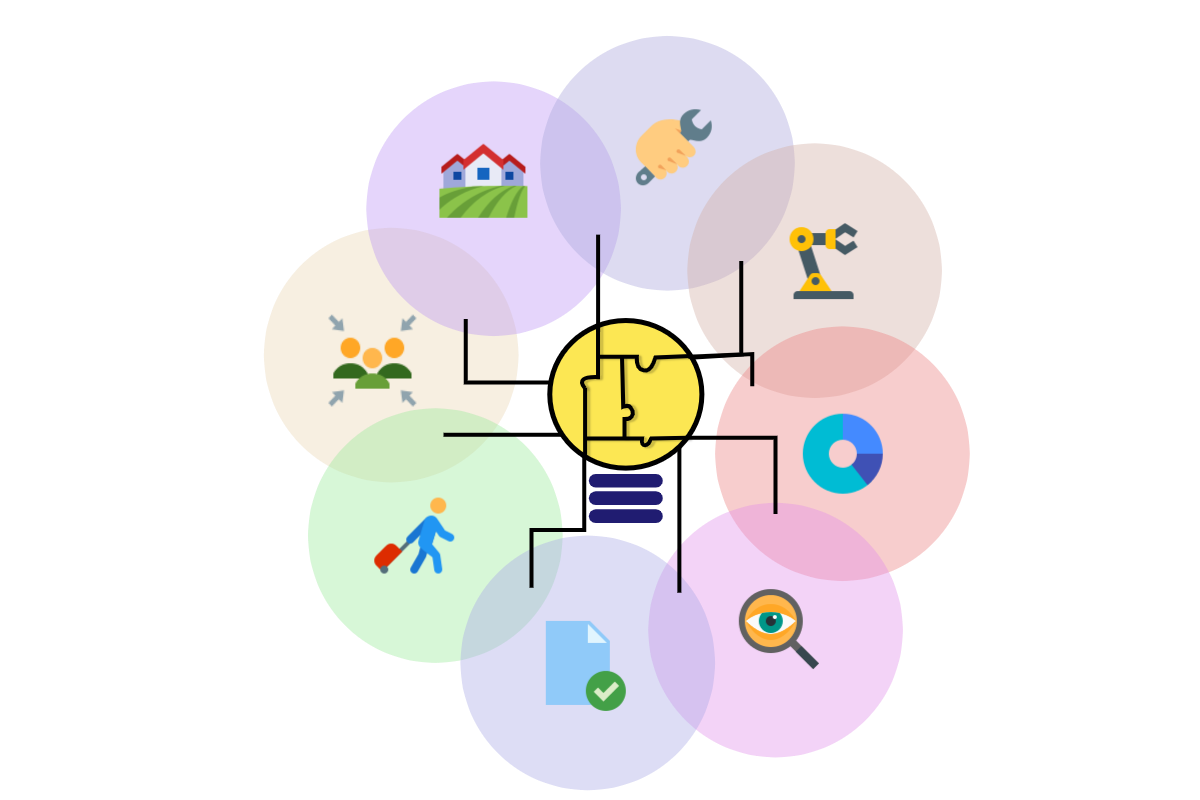

A: Design Jatra is a community organization. We are essentially a group of architects who came together to explore what opportunities architects can unfold in the rural sector, importantly looking beyond building and focusing on the holistic development of the people through participatory development. Briefly, we work in four areas; one is our work with the community to help them grow as a unit by following a bottom-up approach to development. Secondly, we work with natural materials by understanding how they can be integrated with rural architecture; we have clients ranging from the Tribal community to people wanting to build resorts to people wanting to build homes. Thirdly, we engage with many students; usually, the students in cities are exposed merely to urban architecture, however, the rural sector also has a lot of insights to offer that must be spoken about; we are building a community of students who wants to explore rural architecture. Lastly, we are an ecological architecture practice; where we explore architecture in its larger ecological context.

- What was the inspiration behind the practice?

A: We are taught by Architect Malak Singh Gill, his expertise and interests are in creating mud homes, at least that’s all we initially knew about his practice. Later on, he introduced us to the ecological aspects of buildings, and the workings of community engagement. Learning about his work and methods was the first leg of our inspiration. In parallel, our team was researching and traveling the rural sector of Maharashtra, specifically the Dahanu region. During those visits, we met with different people and organizations who were closely working with the community; these folks largely contributed to our drive.

Furthermore, the context itself is the inspiration. We observed methods of the tribal practices and sustainable lifestyle- some of which the sustainable practitioners would dream to achieve- the people living in rural areas practice indigenously; the context that we found ourselves working in, is inspirational in itself.

- What exactly is a socio-architectural practice?

A: From the beginning when we started the practice, especially for the first two years, we built little, our primary focus was to understand the integration of architecture with the context that we were in. We wanted to know how relevant a trained architect is to a context of a tribal village, where people are building by themselves. Our research and interaction with the people of the community concluded that within the context of the tribal/rural sector, a trained architect cannot simply be an architect. The mainstream notion of the architect as a hyper-specialized professional who simply designs deem irrelevant. We realized architects who want to work in the rural sector must advocate for the needs and rights of tribal people beyond rudimentary building design. They have to talk about; forest preservation, tribal certification, unemployment among tribal youth, inaccessibility of policies to relevant individuals of the village, and many more such issues. Such advocacy makes architecture as a profession relevant in tribal/rural contexts. Hence the term 'socio-architectural' practice. Wherever we work, be it in the home village of Design Jatra or a new community, we make sure to establish the link between architecture and society, primarily through community engagement. We ensure to employ local laborers, we engage in interactions with the villages even before the design process; so by the end of a project, we are one with the village. With every project, we try to build a healthy community and not just construct a building.

Furthermore, considering the multi-layer impact of architecture on any given context, the building architecture is a huge responsibility. We try to see the purview of our practice through the perspective of people; how the people respond to it, and whether the structure is alien to them or is there acceptance. To implement our approach of ‘socio-architectural’ practice, we use the toolkit of participatory methods of design and construction.

- What are the challenges you face while establishing a practice in rural development?

A: The primary challenge was building trust within the community. In a tribal context, there is a stigma associated with urban-educated individuals, as we are outsiders and given that the community is distant. At times, as part of our research, we would ask the community certain questions, and they, rightly so, would wonder about our deep interest in their lifestyle and be suspicious of our approach. The process of building trust took a long time and tested our patience.

The other challenge was the implementation of our financial model. We did not want to establish the practice as a non-profit, we were clear from the very beginning to make our practice a 'for-profit' self-funded organization. A typical NGO would start handing out support in terms of a free toilet, free dustbin, free stationery, etc. We were very clear since the beginning to distinguish ourselves from traditional NGOs, we did not want to hand out free goodies/services; we want to foster economic empowerment. But since it is usual for tribal communities to receive services from NGOs, it was challenging to shift the approach.

Another challenge was hopelessness; the tribal youth does not see any potential in their context. Hence, to regenerate the idea, that there is hope in the context, that there is strength in tribal beliefs, tradition, and culture, is a large hurdle.

Another challenge is on a personal front- telling our families what exactly we were doing. Trying to convince them about our travel to and fro from city to village was challenging, however, they have come around and are more accepting.

- As a firm, you have also expanded into a social enterprise called “Tokar Bamboo Ecoart". Please tell us about it and why was it necessary for you to explore that space and how it aligns with the core value of your firm.

A: Initially, we had very rigid ideas of sustainability; it was limited to building mud homes, or say organic farming. Upon observing tribal families, we learned that a family of six comfortably operates on 2000 INR a month and they don’t reside in mud homes, yet they follow a sustainable lifestyle. For some years, we were not able to have an interesting dialogue with the community, primarily because we were trying to impose our ideas of sustainability on them. Our breakthrough happened when we understood that for tribal families financial sustainability comes first. Once that is addressed then you can strike a dialogue about the environment, political sustainability, or sustainability with governance.

To address financial sustainability, we came up with the idea of Tokar Bamboo Ecoart. There is potential in the context, within the culture and tradition of the tribal village. We collaborated with the villagers and introduced a line of products to be sold in the open market. All products of Tokar Bamboo Ecoart use natural and vernacular materials. Design Jatra designs the products and markets them, whereas the villagers execute the design, control quality, mobilize labor, and take care of finances and records. In the long run, we would like to also transfer the role of marketing to them. The key idea is to provide a channel in the community for those who would like to utilize their skills and build a livelihood.

Another aspect of Tokar Bamboo Ecoart was rejuvenating dependency on bamboo in the village. When we built one of our first designs in the village, we wanted to use bamboo in the construction, since the material is indigenous to the area. However, we quickly realized that villages have lowered the production of bamboo since steel pipes were available as an alternative. This sparked a brainstorming session within Design Jatra to reutilize the simple and prime resource of the area, the bamboo. We worked with the tribal youngsters of the self-help group Bachat Gat who were skilled in working with bamboo. Thereafter, through Tokar Bamboo Ecoart, we designed architectural stationery to be sold that was primarily made from bamboo. The design received great traction through social media. Inspired by the success of the product, the youths of Bachat Gat started growing bamboo in their backyard.

- What are some current discussions going on at Design Jatra and the community level?

A: The youngsters who are working with us want to talk about political sustainability. This is a new area for us and we don’t know if we should be putting this under the head of Design Jatra, but I can speak with certainty that we are working on it. The idea is to strengthen the Gram Sabha of the village. We regularly conduct meetings with the youngsters, we are trying to give them a voice.

The dead end to any sustainability program i.e. good forest, good water, good ecology, and good financial sustainability is corruption. We are trying to set things in the system where government policies can be implemented better in non-corrupt ways. When policies are not implemented properly, the tribal people don't speak up against the government due to fear and/or oppression, it has been years since any of them have spoken up about these malpractices.

Simple tools like filing an RTI, investigating policy implementation, and holding the Gram Sevak accountable for financial spending are part of our awareness program and activism. To further our efforts we might have an extension of Design Jatra just like our enterprise Tokar Bamboo art, we don’t know yet. The key idea is to talk about sustainability when it comes to governance.

- How does one go about funding community projects in rural development? Do you make use of national and regional policies or external funding from organizations? Or a combination of both?

A: When we started Design Jatra, we wanted to be a non-funded independent organization and we have remained so. We don't access external funding. An example is recent; villagers decided that for all the activities (for RTI filing, document preparation, traveling, etc.) the community should pool money. Tokar Bamboo Ecoart is another example of how the community has remained economically independent. As for Design Jatra services, we have been gathering money as and when we work for multiple clients.

- Design Jatra transcends beyond the rudimentary services offered by architects, what role do you think architects play in social change?

A: As just a building architect, we don't think we are playing a strong role in social change. Our role largely lies as a facilitator for instrumental services we offer within the community. Within that, we see ourselves as a catalyst, where, since our team comes from a professional perspective, we try to accelerate the processes. Even in our private project, we play the same role.

We manage different agencies, interact with the locals, and bring the community together. Our designs are simple, we take ideas from the locals and are open to dialogue and change. Unlike most architecture firms, we don't want our structure to look in a particular way or style, we are merely the facilitator with the agenda of bringing together different stakeholders of a project. Design Jatra brings ideas to the table, then the different stakeholders who mold the ideas into a project-we are simply the facilitator.

- Design Jatra works with communities through a public participatory processes-an approach that is increasingly becoming popular in architecture and urban planning. How can the educational system in architecture infuse the shift to a participatory process to make it an important tool for architects?

A: The first and foremost thing that colleges need to do is give exposure to participatory processes. As per our college experience, in architecture schools, the profession is put on a pedestal-good or bad-the burden needs to be taken away from architecture students so that they can explore different ways of practicing. Since there are many aspects at play, an architect cannot be the sole designer of a project. Considering this is not the usual practice, then there are debates about the architect's ego that comes from the idea that architects are the decision-makers. We must break through these ideological barriers and shift to a softer approach to architecture through community design. This shift is necessary because an architect as one person is expected to design spaces across the country, no matter the access to data or knowledge, you are not equipped as an individual to gauge the perspective. You are required to interact with the locals, and invite participation from the community in the designing process.

From college itself, students should be taught to interact with the community even before the start of the design process. At the college level, you may not dwell on the details of the participatory process, however, simply making the design participatory would be a big achievement. Students must engage in at least one project where they participate with the people to design by taking climatic, spatial, and temporal inputs from the community. This will cultivate empathy. For participatory processes, the facilitator needs a lot of empathy, and this kind of empathy comes through dialogue with the community.

In colleges, there isn't enough sensitization towards taking such an approach and that must change. Unlike what is taught in colleges, architecture isn't a personalized process for an architect; you as an architect are always designing for someone else, and you must open up the dialogue to others involved in the project. To sensitize students, they must be exposed to the context; architecture students must come out of the classroom often and try to connect with the communities.

- What is your message for young architects who would like to work in rural development and practice in rural India?

A: We are exploring and are a very young practice, we are learning as we are going, but the one primary message we would like to give is to travel a lot. Just pack a bag and take impromptu tours. This is how we started as Design Jatra, travelling helped us in our thinking. We traveled for 6 months every weekend to different villages in our district to understand various lifestyles. Importantly, most students have the luxury to do the traveling since there isn't much social pressure. The best thing young architects can do for themselves is travel, especially to explore uncomfortable places; places you haven’t been before, places with no pakka homes, places where there are no four walls. Travel not for social clout, but to learn. Travel not to see places, but to meet people.