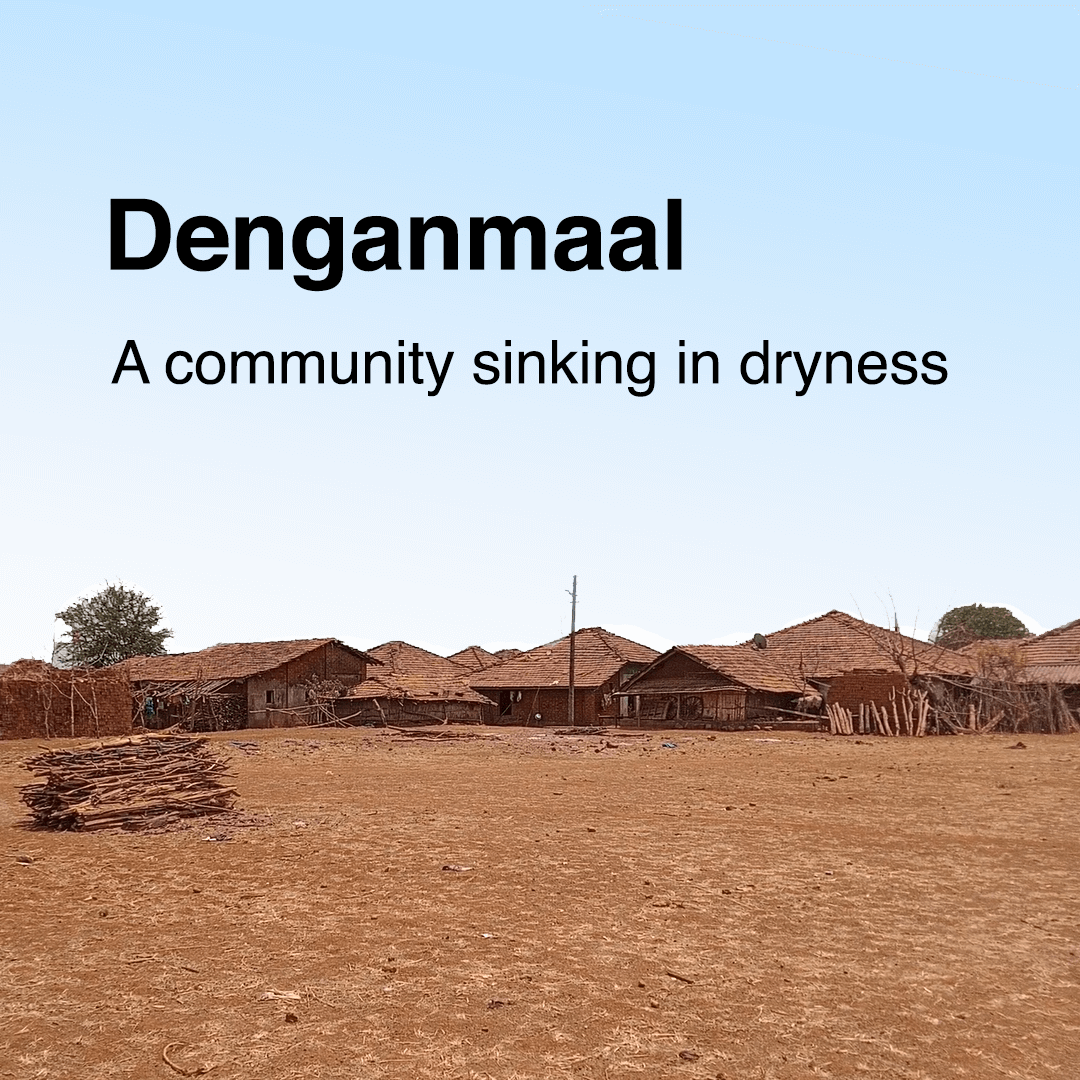

Denganmaal - A community sinking in dryness

Do you use water daily? If you are a human reading this, you might find the question ridiculous. For humans and all other living beings, water is essential for life. A resource held so precious that is often referred to as the ‘source of life’. I am a city girl and live in a municipal ward that provides water 24*7 to my apartment. I and millions of others in my city—not referring to those who live in areas with inequitable water distribution—do not have to stop and think twice to fill up a cup of water from our household taps. I do not schedule my day around my water procurement needs. I do not have to choose between going to work/school and standing in line for hours to get water. For me, water runs in the tap daily, it is available when I need it, in different quantities, and at different temperatures. For me, water is a resource I can count on. However, such is not the case for everyone.

Some 1.1 billion people worldwide lack access to water, and a total of 2.7 billion find water scarce for at least one month of the year (World Wildlife Fund). 900 million in rural population, globally, lack access to basic water supply and sanitation (UNESCO 2015). Many rural areas supply water to the big cities; however, they continue to face alarming water crises, and this is referred to as ‘geographical disparities’. Inequalities persist in terms of geography, socio-culture, and economic status, between rural and urban areas. Rural water supplies have traditionally been overshadowed by urban ones (Omarova et. al 2019). Today, the water crisis in rural areas is due to the rapidly changing climate, population explosion, increased urbanization, migration, and unsustainable practices. It is a global issue. Add to that, the water crisis is not just limited to access, it is a complex issue. Water crisis often exasperates social-ecological issues. Extreme poverty, absence of education, health degradation, and gender inequalities are a few of the issues that are exasperated due to a lack of water infrastructure. To understand this global issue, we look at a community in Maharashtra, a western state in India, to understand how a lack of local and regional sustainable water infrastructure exasperate social issues. This article intends to highlight the plight of a community while addressing a global crisis and importantly engaging with the issue with a solution-oriented approach.

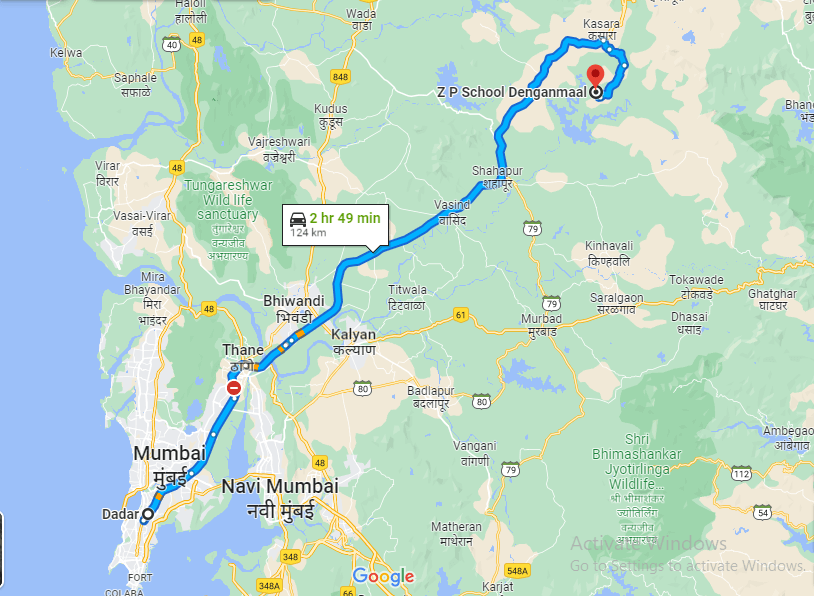

Denganmaal is a small village located in the Shahpur District of Maharashtra, India. It is located approximately 120 kilometers away from the metropolitan city of Mumbai.

Credits: Google Maps, accessed on April 2022

The Bhatsa reservoir—which supplies water to Mumbai City—is located approximately three kilometers away from the village. The village is located at a height of 125 meters from the reservoir basin.

Credits: Google Earth Pro, accessed on April 2022

In the month of July, the region receives maximum rainfall. Annually, Shahpur receives a total of 2600 mm rainfall. Yet, Denganmaal is a water-deprived village. During summers and winters, villagers often find themselves not having enough water to bathe, drink, wash, clean, and farm.

We traveled to the Denganmaal village in April 2022 (the beginning of summer in India). From Mumbai, it took us a total of 3.0 hours to reach the exact location. The closest railway station is Kasara located on the Central local train network of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. From the Kasara station, a few shared taxis are available that take you right up to the village, if you are lucky that is, or as it happened to us, take a ride from one of the JCBs which are currently spotted around the Kasara station due to ongoing work for the Nashik–Mumbai highway extension project. Following that, one might have to trek some odd 5-6 kilometers to reach the exact location. The location is also directly approachable via Washala road which ends up at ZP School Denganmaal.

The hottest days in the Denganmaal village are reported to reach up to 43 degrees Celsius. On the day we visited, the highest temperature recorded was 42 degrees Celsius. The gust resembles ‘loo’-a strong, dusty, gusty, hot, and dry summer wind. The landscape is dry, and the heat is unbearable.

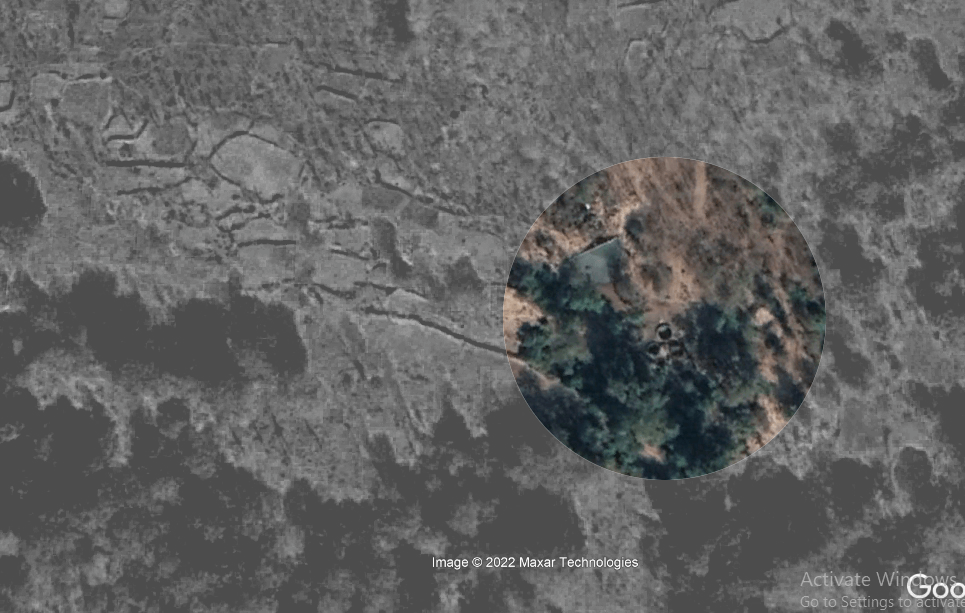

Credits: Google Earth Pro, accessed on April 2022

The dry landscape en route Denganmaal, ©Saba Serkhel

Entry to Denganmaal village, ©Saba Serkhel

The village is located in the Shahpur region of Maharashtra. Almost all villages of the Shahpur region face water issues. The irony is that the Shahpur region provides water to a mega metropolis - the Mumbai City, yet its residents continue to face a water crisis. Mumbai city has a population of 20 million. Shahpur region serves a significant portion of the water demand. In Mumbai, the Vaitarna and Tansa dams supply 455 million liters of water each day, while the Bhatsa dam in Shahpur supplies 2,050 million liters. Shahpur region is fairly able to provide water to Mumbai every year.

Even though the Shahpur region is surrounded by large dams, many villages have been facing water shortages for the past few years. Due to years of drought, rivers' currents have ebbed, and dams and reservoirs have been depleted (Times of India 2022). Times of India (TOI), in 2017, reported decreasing water level in the Thane district. Shahpur region falls within the municipal boundary of the Thane district. As reported by TOI, "Shahpur along with Murbad has the highest number of areas that have reported a drop in groundwater levels over the last five years". The issues cited are rapid urbanization and drilling of bore wells. "Experts have warned if this trend continues the drop in water levels can possible reduce the productivity of land and render it barren in the years to come" (Times of India, 2017).

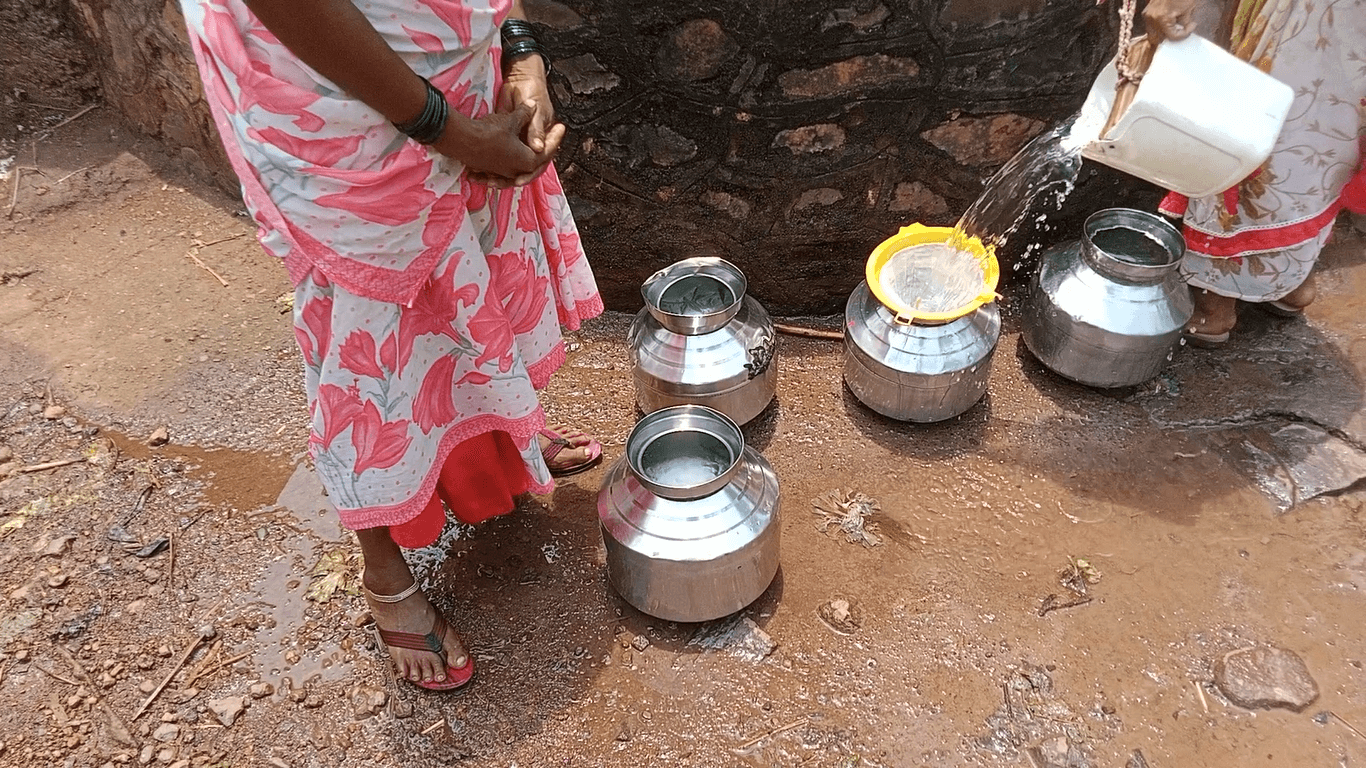

Due to the aforementioned regional conditions, residents of Denganmaal face issues such as reduced groundwater levels, and decreased water retention. As mentioned earlier, the Shahpur region receives an annual rainfall of 2600 mm, however, most of the water retained for the region in the Bhatsa reservoir is siphoned off to Mumbai. The water crisis began approximately three generations ago, earlier, the small wells had enough water within them throughout the year to cater to the needs of the villagers (as per accounts of the locals). However, due to a lack of local water retention methods, and the practice of siphoning water to Mumbai, the groundwater of Denganmaal is not recharged, and hence the main source of water is the just two—barely filled—wells located at the foot of the village.

Map showing proximity of wells to the Denganmaal village, credits: Google Earth Pro, accessed on April 2022

Aerial showing the wells of the Dengaanmaal village, credit: Google Earth Pro, accessed on April 2022

Women filling containers with water near one of the two wells ©Saba Serkhel

The path to these wells is rocky. The wait for one's turn is in hours. During summers and winters, the wells do not fill enough to provide for everyone's needs. The task of daily water procurement is taxing both physically and mentally.

The village first came under the international limelight when the late photojournalist Danish Siddique released photographs of the community through Reuters. The article was titled 'Drought-hit Maharashtra village looks to 'water wives' to quench thirst'. Following his publication, other internationally renowned newspapers also covered the infamous story of the water wives. The lack of water has resulted in many social issues. Covered by Danish and others is that of gender. It is a common opinion and conclusion of many researchers that water issues disproportionately impact women across the globe.

The issue persists as in most cultures the task of obtaining the water is a woman's job. The women of the house (usually the mother and the daughter) are tasked with the taxing chore of procuring water from miles away for the entire family while giving up their personal lives. Young girls often miss school and the elder women often report physical ailments. Similar is reported in Denganmaal. However, the issue complexes further. Men of Denganmaal marry two-three women and practice polygamy solely to ensure water procurement. “I had to have someone to bring us water, and marrying again was the only option,” said Bhagat, who works as a day laborer on a farm in a nearby village. “My first wife was busy with the kids. When my second wife fell sick and was unable to fetch water, I married a third.” (As reported by Reuters, 2015). This has become a sub-cultural norm in the village. It is to be noted, that in India polygamy is illegal and not reported commonly anywhere. However, due to water scarcity, polygamy continues to persist in this village. Upon interviewing the women it is understood that the older generation of women is accepting of the arrangement. They see it as their way of contributing to easing the burden of the water crisis. However, the younger generation wants to marry outside the community and be the only wife.

Add to that, most of the villagers practice farming as their main source of occupation. Agriculture is a water-based occupation, due to a lack of water, farming in the village suffers. They are barely able to farm for themselves let alone engage in the export of produce. Thereafter, in summers, they often resort to working as construction workers. The villagers face water scarcity every summer and winter and along with that issues of extreme poverty, gender inequalities and education are exasperated.

Our investigation and interview with locals conclude that lack of water was a common cry. When inquired about what had changed since the story broke out, the air was filled with disappointment and frustration. It has been seven years since the Reuters story, and the water crisis is still prevalent. Two years ago, the Shahpur Municipal Authority provided four tanks to the village. The connection to the water (as reported by the villagers) comes directly from the nearby Bhatsa reservoir. However, a year later, the water connection burst open and since then the four tanks in the village remain dry. There is also a bore well installed by the Patol Nagar Panchayat, however, the installed bore well requires electrical power. The village does not receive enough electrical power that can support the bore well system. Hence, it also remains dry.

A man poses next to one of the four water tanks ©Saba Serkhel

The village is back to square one. It now only has the two original wells (constructed some 25 years ago) as the primary source of water. Albeit rarely, the villagers also travel down to the Bhatsa reservoir to collect water.

Google map showing the proximity of Bhatsa reservoir to Denganmaal village, accessed on April 2022

Our focus is to tackle the root cause of the issue, which is ‘scarcity of water’. Improvements in water availability in Denganmaal will certainly have positive social impacts. Hence we investigated the issue with two main agendas:

-

To understand the current scenario (Danish reported the issue in 2015, we wanted to understand what remains or changed in 2022) and dive deeper to understand how local, and regional lack of infrastructure exasperate social issues.

-

Brainstorm local-level solutions with the community to tackle water scarcity and gender inequalities.

Suggested solutions:

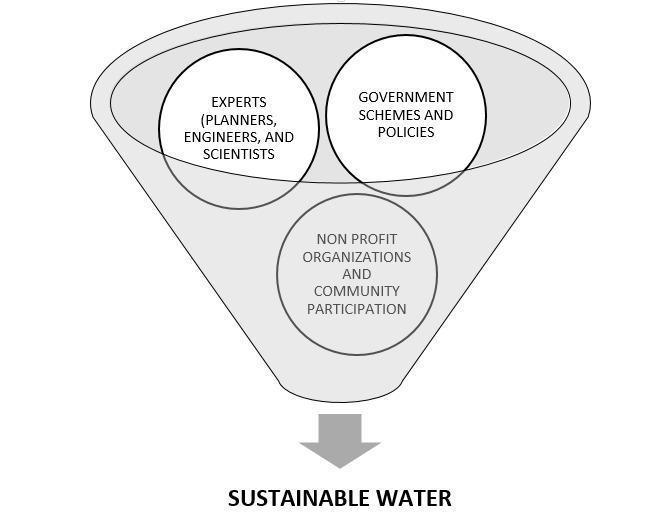

The suggested plan of action can be classified within three heads:

For the Denganmaal community: The village needs a sustainable plan of action to improve the ecology of the area. Suggested ideas include water retention (creating a local small reservoir that supplies year-round water supply for the village) and recharge of the groundwater table. The agenda is to plug in vernacular water infrastructure to meet the gaps in the socio-ecological aspects discussed above.

- Water retention: The village is situated on an elevation, thereafter, towards the west side, there is a natural flow of water. Few small streams are also reported during the monsoon season. The village requires demarcation and proper construction of a local water retention pond. Additionally, it would also require a solar-powered pump system to ensure that water from the retention pond reaches communal taps in the village. Moreover, water is also required for agriculture purposes. During summer, it is challenging to farm due to a lack of water. We suggest creating a network plan of retention ponds near the agricultural fields.

- Recharging groundwater: Currently most of the water run-off is directly deposited in the Bhatsa reservoir. The Denganmaal village requires stormwater management to ensure a decrease in water run-off. A simple yet effective solution is the method of natural contour bunding. The area needs a detailed contour study to demarcate zones where natural contour bunds can be formed. These bunds are effective in retaining water thereafter reducing water run-off and recharging the groundwater table. Paani Foundation has effectively used this technique in Satara District to successfully tackle the water crisis.

- Regional Level: Shahpur taluka requires a long-term 'sustainable water infrastructure plan' to tackle region-wide water scarcity. The plan's agenda should aim at meeting the current needs of the residents as well as improving and nurturing the ecology for the future. A region-wide water mapping is imperative. In addition, a suitability analysis to map and select land cover for water retention and detention ponds is a must. A thorough understanding of soil mapping and ecology is important. A well-analyzed proposal of a network of water retention ponds needs to be carefully implemented for water storage, water regulation, soil, and biodiversity protection. We suggest a well-networked plan of water infrastructure that includes, water retention ponds, protection of biodiversity, permaculture, revived protected lands, the inclusion of renewable technologies, and increased natural land cover.

- Gender-inclusive: The water scarcity in the Denganmaal village brings into light an important issue; water scarcity disproportionately impacts women across the globe. To tackle the impact at the community level, women need to be involved at the center of decision-making and project execution. A project in the Vellore district of Tamilnadu is exemplary in this case. Female farmers in the district worked as leaders and executives to revive a dry river and consequently transformed the ecology of the village (Saranya C, 2019). Similarly, women of Denganmaal need to be appointed to leadership and included in the decision-making of infrastructure projects—especially water infrastructure. A skill development program and leadership orientation workshops must be held in the village for the empowerment and betterment of the residents. Women are double marginalized in the region, to ensure holistic development of the socio-ecological aspects, the plan must include an equitable gender empowerment program.

Women of Vellore working for Naganadhi River Rejuvenation Programme, credits: https://vellore.nic.in

Call for Action:

The team at WOARCHITECT has conducted a preliminary study and report. The project requires detailed studies, infrastructure planning, and community participation. It needs the assistance of NGOs, government, residents, and experts (architects, engineers, scientists, and urban planners). This article is a call for action. The intent is to highlight a global crisis whilst focusing on a community and approaching the issue with a solution-oriented approach. We request you to engage with us and help ensure that the issue is mitigated and eventually resolved completely. We hope to create a network of experts, communities, and institutions that can assist Denganmaal and other padas of Shahpur taluka in tackling the water crisis.

Write to us at editor@woarchitect.com to participate and assist in the project.

About the Author:

Saba is an architect-planner from Mumbai City. Currently, she is making a documentary that explores the water crisis in rural areas of Maharashtra. As a passion project, she also has a podcast, created with a friend. Their podcast discusses urban planning issues that are neglected in mainstream academic spaces, titled "Lettus Talk". She also makes comics exhibiting her work on the social handle @saba_serkhel. To present her thinking efficiently, Saba explores avenues of expression through various mediums. To reach her, write to serkhels@gmail.com

Reference

The Asian Age. (2019, May 12). Shahapur reels under water scarcity. The Asian Age. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://www.asianage.com/metros/mumbai/120519/shahapur-reels-under-water-scarcity.html

Coles, A., & Wallace, T. (2005). Gender, water, and development. Berg.

Deccan Chronicle. (2019, August 25). Every drop counts: Maharashtrians in Shahapur Taluka struggle for water. Deccan Chronicle. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://www.deccanchronicle.com/gallery/nation/130519/every-drop-counts-see-people-of-shahapur-taluka-in-maharashtra-struggle-for-water.html

Farhana Sultana (2009) Fluid lives: subjectivities, gender and water in rural Bangladesh, Gender, Place & Culture, 16:4, 427-444, DOI: 10.1080/09663690903003942

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD. (n.d.). Ground water information thane district Maharashtra. Retrieved April 26, 2022, from http://cgwb.gov.in/district_profile/Maharashtra/Thane.pdf

Kapur, M. (2015, July 16). Indian men marrying multiple wives to help beat drought. CNN. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://edition.cnn.com/2015/07/16/asia/india-water-wives/index.html

Kohli, A. (2015, November 30). India's 'water wives.' A hard truth told in a short film. NDTV.com. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://www.ndtv.com/offbeat/indias-water-wives-a-hard-truth-told-in-a-short-film-1249243

Manoj Badgeri / TNN / Dec 3, 2017. (n.d.). Alarming drop in underground water stock; Thane district levels at 5-Year low: Thane News - Times of India. The Times of India. Retrieved April 26, 2022, from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/thane/alarming-drop-in-underground-water-stock-thane-district-levels-at-5-year-low/articleshow/61896672.cms

Omarova A, Tussupova K, Hjorth P, Kalishev M, Dosmagambetova R. Water Supply Challenges in Rural Areas: A Case Study from Central Kazakhstan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Feb 26;16(5):688. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16050688. PMID: 30813591; PMCID: PMC6427320.

Paani Foundation. (n.d.). Stories of social change and unity: Paani foundation impact. Paani Foundation. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://www.paanifoundation.in/impact/stories-of-change/

Person. (2016, May 18). We cater to Mumbai, where is our share of water: Shahapur residents. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/mumbai/we-cater-to-mumbai-where-is-our-share-of-water-shahapur-residents/article8613893.ece

Rueters. (2016, April 20). This story of Maharashtra's water wives is as heartbreaking as the drought itself. IndiaTimes. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://www.indiatimes.com/news/india/this-story-of-maharashtra-s-water-wives-is-as-heartbreaking-as-the-drought-itself-253278.html

Rural Water Development. UNESCO. (2015, February 19). Retrieved April 26, 2022, from https://en.unesco.org/themes/water-security/hydrology/water-human-settlements/rural-development

Sanjay Hadkar / TNN / Updated: Apr 10, 2022. (n.d.). Shahpur: Maharashtra: It's dry days for Shahpur villagers; dams nearby, but not a drop to drink: Mumbai News - Times of India. The Times of India. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/mumbai/maharashtra-its-dry-days-for-shahpur-villagers-dams-nearby-but-not-a-drop-to-drink/articleshow/90756058.cms

Saranya Chakrapani / Updated: Jun 19, 2019. (2019, June 19). How 20,000 women in Vellore got together to save a dying river: India News - Times of India. The Times of India. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/how-20000-women-in-vellore-got-together-to-save-a-dying-river/articleshow/69850795.cms

Siddiqui, D. (2015, June 4). Drought-hit Maharashtra village looks to 'water wives' to quench thirst. Reuters. Retrieved April 26, 2022, from https://www.reuters.com/article/india-waterwives-maharashtra-idUSKBN0OK1CI20150604

Siddiqui/Reuters, D. (2015, June 5). The water wives of Maharashtra – in pictures. The Guardian. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2015/jun/05/water-wives-maharashtra-india-in-pictures

Smita Mishra Panda (Professor of Development Studies) (2007) Mainstreaming Gender in Water Management: A Critical View, Gender, Technology and Development, 11:3, 321-338, DOI: 10.1177/097185240701100302

TOI.in. (2022, April 10). Shahapur: Women walk 3 KMS Daily in Maharashtra's Shahapur to fetch a bucket of drinking water: Toi original - times of India videos. The Times of India. Retrieved April 26, 2022, from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/videos/toi-original/women-walk-3-km-daily-in-maharashtras-shahapur-to-fetch-a-bucket-of-drinking-water/videoshow/90760291.cms

UN. (2019). UNITED NATIONS World Water Development Report 2019. UN WATER .

World Wildlife Fund. (n.d.). Water scarcity. WWF. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://www.worldwildlife.org/threats/water-scarcity#:~:text=Billions%20of%20People%20Lack%20Water,may%20be%20facing%20water%20shortages.